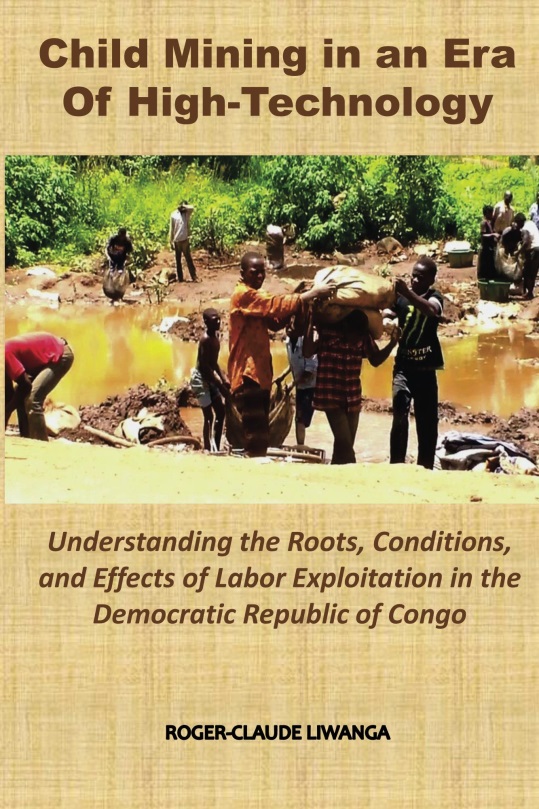

About the Book

This book is about “child labor exploitation.” The book argues that mining work is one of the worst forms of child labor because the working conditions in the mines are harmful to the health, safety, education, and development of child miners. It also contends that a combination of factors drives children to work in the artisanal mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). These variables include poverty; adult unemployment; lack of educational opportunities; sociocultural conditions; lack of law enforcement; and globalization with its high demand for mined minerals and cheap labor.

The book also alleges that child miners in the DRC contribute significantly in the production of a variety of raw minerals, such as cobalt, coltan, and tin, which are used in the process of fabrication cell phones, computers and other modern electronics. For example, children involved in cobalt mining in the DRC produce about 7.5% of the world’s total production of cobalt. The employers and corporations that source minerals from child miners reap high profits while paying children extremely low wages.

The book concludes by suggesting the adoption of a comprehensive approach to eradicate child mining labor in the DRC. This includes the reduction of poverty, the creation of alternative opportunities for child miners, the enforcement of free education in remote mining areas, the prosecution of child labor-exploiters, the traceability of mined minerals, and public awareness-raising on the slavery-like situation of child miners. Some of these strategies have been adopted in countries that previously had a high prevalence of child labor, such as Brazil, Kenya, and the Philippines. As a result, the prevalence of child labor significantly decreased in those countries.

About the Author

Roger-Claude Liwanga is a human rights lawyer from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). He holds a doctorate of juridical science (SJD) in international law degree, and is a Fellow on Human Trafficking and Forced Labor with the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard University. He taught international law of war at Suffolk Law School- Boston in Spring 2016, and was a Visiting Scholar with the African Studies Center at Boston University. He has also consulted with the Carter Center and the American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative on human trafficking and other human rights issues in Africa. Liwanga is also the author of numerous articles published in peer-reviewed journals, and a contributor to The CNN Freedom Project, The Global Post and The Cape Times. His documentary “Children of The Mines” aired on the ABC television affiliate (WCVB TV) in Boston.

Peer Review and Comments

Human rights attorney Roger-Claude Liwanga reveals the painful truths that lead to Congolese children working in hazardous mines – “free education” that is not free; severely impoverished families that can neither pay for school nor survive without their children working; a government legally obligated to protect children and prosecute traffickers but does not because it is rife with corruption and revenue short; and affluent countries that consume commodities, produced in part with raw materials mined by trafficked children, while ignoring the supply chain. Liwanga gets it! He has conducted extensive research including face to face interviews with all the critical players without a preset agenda.

Susan L. French – Former U.S. Department of Justice Human Trafficking Prosecutor

A well-researched book, which has highlighted issues concerning the exploitation of child miners in Congo. A powerful story, which also throws light on the psychological and physical abuse of children and a shocking number of children’s deaths a year! Human right organizations and educational institutions will find this book really beneficial, informative and revealing.

Jai Sharma – Chairman, World Commission of Human Rights

This book reveals the dilemma of craving the latest technologies (phones, tablets and laptops) without understanding high human cost paid to extract the natural resources to create these commodities; particularly the human tragedy of exploiting of child labor. The sociological factors that contribute to a climate in which child mining can flourish is clearly documented by Dr. Liwanga. He masterfully weaves a story of the plight and exploitation of African children and the burden child mining places on the Congolese family unit.

Dr. Alicia Simon – Assistant Professor of Sociology, Clark Atlanta University

I was not even out of the introduction and into the pages with real numbers before being taken by the approach, the issues of course, which is strongly in focus for slavefreetrade, and the innate difficulties in both getting inside the business and then doing something about it. This book reminded me (again) of the complexity in applying some of the most fundamental principles of human rights law.

Brian Iselin – Founder | President, Slave Free Trade

Sample Excerpt from the Book

CHAPTER THREE

Working Conditions and Fate of Child Miners

A Conversation with Creuseurs in an Open-Pit Mine in Musonoi

Photo 3.1: Open-pit mine of Musonoi.

In that warm morning of 2013, I climbed an estimated terrain of 1,459 meters (about 4,787 feet) above sea level[i] to reach the peak of an open-pit mine in Musonoi. There, I saw many groups of creuseurs (mine diggers) who were digging for ores at different places. Each group of miners that I met had at least two members. One of the first creuseurs I spoke with on that day was named Marco. When I saw him, Marco was holding an iron shovel of about four feet long next to a hole that was seven or nine feet deep. What was a bit strange was that Marco was working alone; I did not see anyone else around him. I was intrigued and approached him to inquire if I could ask him some questions, to which he gently agreed. Our conversation was held concurrently in both French and Swahili.

“How old are you?” I asked.

“Fifteen years old,” he responded.

“What is the tool that you are holding?”

“A shovel.”

“What do you use it for?”

“To dig up to extract ores.”

“But the hole you are digging is getting quite deep. Aren’t you concerned that it can be dangerous for you if you get in and keep digging further?

“Yes, I know that. But, as you can see, I started to prepare and create rooms inside of the hole before carrying on with digging.”

“How can you further dig while you are working alone?”

“No, I am not really alone. I work with my uncle. He is over there, the other side of the mine. He will come back to join me.”

In speaking about the “rooms” inside of the hole, Marco was referring to corridors that miners usually create underground when they reach some depth; these corridors may be connected with other holes underground. But I do not understand any correlation between the digging of these underground corridors and the prevention and protection of miners against soil collapse.

About two hundred feet from Marco’s mining hole, there was another group of three creuseurs who had just started to dig another hole. They were digging in a rocky spot and their hole was about five feet deep and six feet in diameter. They told me that they had only been digging for a couple of hours; but they seemed to me very tired as if they had already worked for the entire day. I jokingly asked one of those miners, the one who was on the surface, if I could help them to dig. He looked at me, smiled, and said “yes” while nodding. He told his colleague who was working at the bottom of the hole to get out, and to leave the iron pick that he was using inside of the hole. I told them that I was only joking, but they insisted that I should try. And I agreed. I jumped inside of that rocky hole with the pair of jeans and climbing shoes that I was wearing on that day. Once inside the hole, I picked up their iron pick and was surprised at how heavy it was. The pick weighed somewhere between twenty-five and thirty-five pounds. After digging for about only one or two minutes, I felt really exhausted and was sweating from everywhere. I also felt a bit suffocated in that hole where the air circulation was deficient. It was truly painful. When I got out, all the creuseurs were smiling. But I did not ask them why. I do not think that their smiles were intended to mock me. Their smiles were meant to convey how difficult mining truly was. It was a way for them to find solidarity in the back-breaking nature of their work.

Later that evening, while I was in my hotel room, I took some pain killers and thought about my mining experience that day. I remember thinking to myself, if an adult person such as I could get quickly exhausted for only mining less than five minutes, then what about the child diggers who work more than ten hours per day?

Working Conditions in the Artisanal Mines

Artisanal mining in the DRC is characterized by poor working conditions. In all of the artisanal mining sites that I visited, I noticed a poor level of mechanization and a lack of minimum standards of health and security. I observed many child miners working with bare hands and feet, and without protective gear.

In artisanal mines, the extraction of mined minerals is done by hand with picks, shovels, and buckets. Artisanal miners are required by law not to dig more than thirty meters (ninety-eight feet) underground to extract ores.[ii] But, some artisanal miners excavate up to 140 meters (460 feet) in tunnels that regularly lack any form of structural support.[iii]

CHAPTER 3 – Endnotes

[i] Geoview, “Musonoi,” (n.d.). http://cd.geoview.info/musonoi,922414

[ii] Law No 007/2002 of July 11, 2002 relating to the Congolese Mining Code [Loi No 007/2002 du 11 Juillet 2002 portant Code Minier Congolais], Article 1 (21).

[iii] Pact, Promines Study: Artisanal Mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Washington, DC: Pact, 2010), 48.

http://www.congomines.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/PACT-2010-ProminesStudyArtisanalMiningDRC.pdf

Book Listing

List Price: $14.95 USD

Size: 6.14″ x 9.21″ (15.596 x 23.393 cm)

Paperback: Black & White on White paper

Length: 124 pages

ISBN-13: 978-0997560336

BISAC: Social Science / Slavery